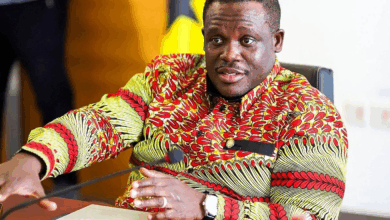

Stories That Matter: Atul Balaji Marewad on Authenticity in Writing and Film

Interviewer:

As someone who has been the Asia & Middle East Coordinator since the foundation of the Accra International Book Festival and who is deeply connected to Accra’s literary landscape, what inspired you to link Indian authors with the festival and build a bridge between the two cultures?”

Atul:

“From the very beginning of my association with the Accra International Book Festival, I felt a strong resonance between Ghana’s literary heartbeat and the storytelling traditions of my own country. Both societies have deep roots in oral history, folklore, and community-based narratives. My aim has always been to create a space where Indian and African writers can meet as equals—sharing raw, real, and rustic literature that speaks to ordinary lives. By connecting authors from India to Accra, I hoped to build a bridge of mutual learning and cultural exchange, so that our literatures can inform, challenge and enrich one another.”

Interviewer:

“You’ve often spoken about your commitment to ‘raw, real and rustic’ literature. How do you define this kind of writing, and why do you believe it is important for readers in both India and Ghana?”

Atul Marewad:

“India and Ghana share many realities as developing nations — complex histories, uneven development, and the everyday struggle for survival and dignity. In such contexts, literature cannot only be about polished lifestyles or imported trends. ‘Raw, real and rustic’ literature, as I see it, is rooted in the soil of lived experience. It is writing that does not shy away from poverty, migration, rural life, informal economies, gender struggles, or existential crises of people on the margins. It values authenticity over glamour and honesty over pretence. This kind of literature matters because it makes invisible lives visible and gives dignity to ordinary voices. It tells readers, in both India and Ghana, that their stories matter, that their pain and aspirations are worth recording. At the same time, it also challenges writers not to lose themselves in imitating distant realities but to stay true to their own communities and languages. Rustic literature, for me, is a way of resisting hypocrisy and alienation; it’s a bridge between people’s real lives and the stories we tell about them.”

Interviewer:

As someone building literary bridges between India and Ghana, what differences and similarities have you observed in the storytelling traditions of the two countries?

Atul: “Both India and Ghana are post-colonial societies, and that shared history gives our literature a similar undercurrent of struggle, identity and resilience. Each country has its own deep roots in oral traditions, myths, folk tales and community storytelling. These forms survived colonisation and continue to shape how we narrate our experiences. In both places there’s a hunger to tell stories of the everyday — of labourers, farmers, market women, migrants — and to question inherited power structures. At the same time, the textures differ: Ghanaian narratives often carry rhythms of West African oral performance, proverbs and communal voice, while Indian narratives are layered with its multiple languages, caste realities and regional diversities. But at their heart, both literatures are about reclaiming agency and dignity for ordinary people. That is what excites me about creating a dialogue between them.”

Interviewer

In your role as Asia and Middle East Coordinator for the Accra International Book Festival, how do you practically connect authors from India with Accra’s literary community?

Atul:

“My work has always been about building actual relationships rather than one-off appearances. Each year I identify Indian writers, filmmakers and academics whose work reflects the kind of authentic, socially rooted literature the festival celebrates. I invite them to the Accra International Book Festival and also to the Accra International Film Festival when relevant. Because of COVID-19 and travel constraints, we couldn’t bring everyone physically to Ghana, but I refused to let the dialogue stop. Instead, I set up virtual sessions where these voices could meet Accra’s readers and young writers. Over the past few years I have connected 10–12 Indian authors, professors and filmmakers to the festival. They have given online lectures, held interactive Q&A sessions, mentored participants and run writing workshops for local audiences. This approach has ensured that, even across continents, we create an active space for exchange, skills sharing and mutual inspiration.”

Interviewer:

“Accra has seen the rise of festivals like the Accra Indie Film Festival, the Accra Animation Festival, Accra Art Week and the Black Star International Film Festival. What do you think can be done — especially by government — to support these initiatives and help young creatives thrive?”.

Atul:

“These festivals are already doing incredible work in giving platforms to independent voices and new forms of storytelling. They are nurturing filmmakers, animators, artists, writers and academics who want to speak honestly about their lives. But for these initiatives to grow and truly change the landscape, they need sustained support. Government can play a huge role by providing more funding, training opportunities and infrastructure for such festivals. That would give students and individuals the confidence and resources to experiment, to innovate and to tell their own stories — through painting, film, literature, academics or even sport. With proper investment, Accra’s creative sector can roar even louder and carry its stories to the world.”

Interviewer:

Which writers or works of literature from Ghana have influenced or inspired you the most, and what draws you to them?”.

Atul:

“I’ve been deeply inspired by several Ghanaian writers whose work speaks directly to lived experience and cultural memory. Bisi Adjapon’s Daughter in Exile and The Teller of Secrets are powerful explorations of identity, belonging and the tension between tradition and modernity. Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing and Transcendent Kingdom moved me with their intergenerational sweep — how they carry history, migration and trauma across time yet still remain intimate and human. Peace Adzo Medie writes with such clarity about women’s lives and social expectations, and Frances Mensah Williams brings a vibrant, contemporary energy to Ghanaian stories in her novels. What draws me to all of these authors is their honesty; they don’t shy away from complexity or pain, but they also show humour, resilience and the richness of Ghanaian life. Reading them feels close, familiar and universal at the same time — the kind of ‘raw and real’ literature that builds empathy across borders.”

Interviewer:

In your view, what should we — as writers, readers, educators and policy makers — do to nurture more authentic and powerful storytelling in Ghana and beyond?.

Atul:

“If we really want authentic storytelling to flourish, we have to create the conditions for it ourselves. We should start our own short-story competitions and independent film festivals dedicated to new voices. We should actively promote countryside literature, regional-language writing and local films, not only in the cities but in smaller communities as well. Writers’ residencies, translation programmes, regular workshops and mentorship schemes can give emerging authors the space and skills to grow. At the same time, new prizes, new platforms and even new institutions — backed with consistent funding — are needed so that these initiatives don’t disappear after one or two editions. When such structures exist, storytellers from small towns and villages can develop their craft, share their work with audiences and keep our cultures alive with fresh, honest voices. It’s about building an ecosystem where authentic stories are nurtured and celebrated at every level.”

Interviewer:

You have a rich background in literature, film, and academia. How do your own projects — like your upcoming novel and film — reflect the values of ‘raw, real and rustic’ storytelling you advocate for?.

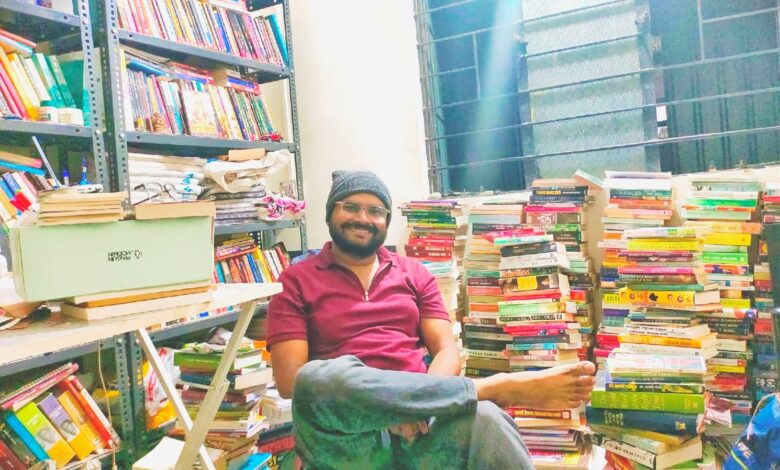

Atul:

“My projects are grounded in the same principles I value in literature and storytelling. They focus on authentic experiences, ordinary lives, and voices that are often overlooked. Currently, I am working on a novel that gives voice to the youth in India’s villages — exploring how they suffer, the problems they face, and how government policies often ignore or even harm them. My aim is to portray their realities honestly, without glamorizing or sanitizing them, highlighting both their struggles and resilience. Similarly, in my film projects, I try to stay true to people lived experiences, ensuring that these stories reflect society honestly and create space for narratives that might otherwise remain unheard.

Interviewer:

What advice would you give to young writers and filmmakers in Ghana who want to tell authentic stories but feel limited by resources or recognition?.

Atul:

“I would say: be authentic to your own stories. Stay true to your identity, your people, and your surroundings. Focus on the realities you know, and tell them with honesty. Support each other, share your knowledge, and create your own platforms if none exist. Even small steps — writing, filming, sharing locally — can grow into movements that amplify overlooked voices. Limitations in resources should not stop storytelling; creativity and community can always overcome them.”

Interviewer:

Looking ahead, what is your hope for the next generation of writers and storytellers in Ghana and across the world?.

Atul:

“I hope the next generation will seed hope through their stories. I hope they remain authentic, honest, and fearless, standing for the voices that have been ignored or silenced. I hope they help each other, build communities, and celebrate stories that matter — stories that reflect real lives, challenge assumptions, and connect people across cultures. Ultimately, I hope they carry forward the power of literature, film, and art to inspire, heal, and transform societies.”

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of Multimedia Group Limited.

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of Multimedia Group Limited.

Source link