One of the World’s Most Remote Islands Is Now More Accessible Than Ever

Saint Helena’s trio of peaks pierce through a sea of cloud, six hours after our flight departs South Africa-a blink of time compared to the six-day sea voyage required until 2017. Located 2,000 kilometers from the continent, and almost halfway to Brazil, this shard of basalt-often grouped with its sister islands, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha, which lie only marginally closer-forms one of the most isolated territories on Earth. What secrets would Saint Helena reveal in the coming days, shrouded in the same enigmatic mist through which it first emerged?

Though best known as the island where Napoleon Bonaparte was exiled and ultimately died, Saint Helena’s historical footnote belies a far richer identity-one rooted in extraordinary natural beauty. When Charles Darwin landed on its shores in 1836 as part of his round-the-world HMS Beagle expedition, he marveled at its otherworldly biodiversity. Saint Helena, he wrote, was a “remarkable” place that “excites our curiosity.” How right he was. Roughly the size of San Francisco, the island is home to more than 500 endemic species of flora and fauna-25 times more per square kilometer than the Galápagos Islands, whcih famously helped shape his theory of evolution.

Stepping onto the tarmac, the first sensation is of alpine-fresh air, laced with a salty fret that drifts in from the South Atlantic. Forged by volcanic eruptions that ceased around seven million years ago, Saint Helena rises dramatically to 800 meters above sea level. I drive north along a steep, slaloming road to Jamestown, the capital-a cluster of Georgian buildings ensconced within one of the deep, narrow ravines that define the island’s singular topography.

Accommodation is limited, but distinctive. I check into the Mantis, which offers understated comfort, with generous terraces and simple decoration, housed in the former officers’ barracks. By contrast, the eccentric Consulate’s façade features ornate wrought-iron balconies and interiors crowded with model ships and portraits of Napoleon. For a more secluded stay, head to Farm Lodge, 20 minutes by car from Jamestown, set within 10 acres of lush tropical gardens. There, a chorus of cicadas rings through the greenery, accompanied by Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony on a crackling gramophone. Owners Stephen and Maureen serve a five-course menu made almost entirely from their own produce, with dinner announced by the ringing of a ship’s bell strung from the verandah.

With a population of just 4,000, the people of Saint Helena-known colloquially as Saints-are nothing if not resourceful. I trace Napoleon’s footsteps with Michel Dancoisne-Martineau, from his first island residence at the Briars-a small, elegant pavilion with shamrock-green walls, tall sash windows, and fireplaces trimmed in gold-to his final one: the palatial mansion of Longwood House. (Exile, it seems, was not much of a hardship.) Our journey ends in the Valley of the Tomb, where Napoleon was laid to rest in 1821 before his remains were returned to France 19 years later. Dancoisne-Martineau, the French honorary consul and curator of the French domains on Saint Helena, is also a gifted artist. His delicate botanical paintings of indigenous plants are sold at the island’s heritage museum-a former powerhouse in Jamestown. Meanwhile, Martin Henry-Saint Helena’s Minister of Health and Social Care-runs a bespoke e-bike tour company in tandem with his ministerial duties.

E-Connect is designed to inspire Saints to return to their not-so-distant past’s active, outdoor lifestyles as much as it is to welcome visitors. Henry has observed a growing dependence on imported, processed food, and a rise in sedentary habits following the introduction of mobile phone services in 2014-both of which, he says, have contributed to a surge in noncommunicable diseases. “Outside influences have, in some ways, derailed our connection to place and nature,” he tells me. “We have lost the ability to walk straight into the landscape. I want to help bring people back to that.” His philosophy is holistic: “If we are not taking care of our internal environment-our physical and mental health-we will never truly care for the external one.”

Henry has also identified ways to improve the island’s diet, noting that most homes on Saint Helena have space for a small vegetable patch or fruit trees-echoing the self-sufficiency seen on a grander scale at Farm Lodge. For coffee lovers, there is Wranghams, an elegant restaurant at the foot of Diana’s Peak National Park, where owner Debbie prepares healthy meals in her open-plan kitchen and cultivates a strain of Arabica unchanged since its arrival from Yemen in 1733-freshly roasted by her husband, Neil.

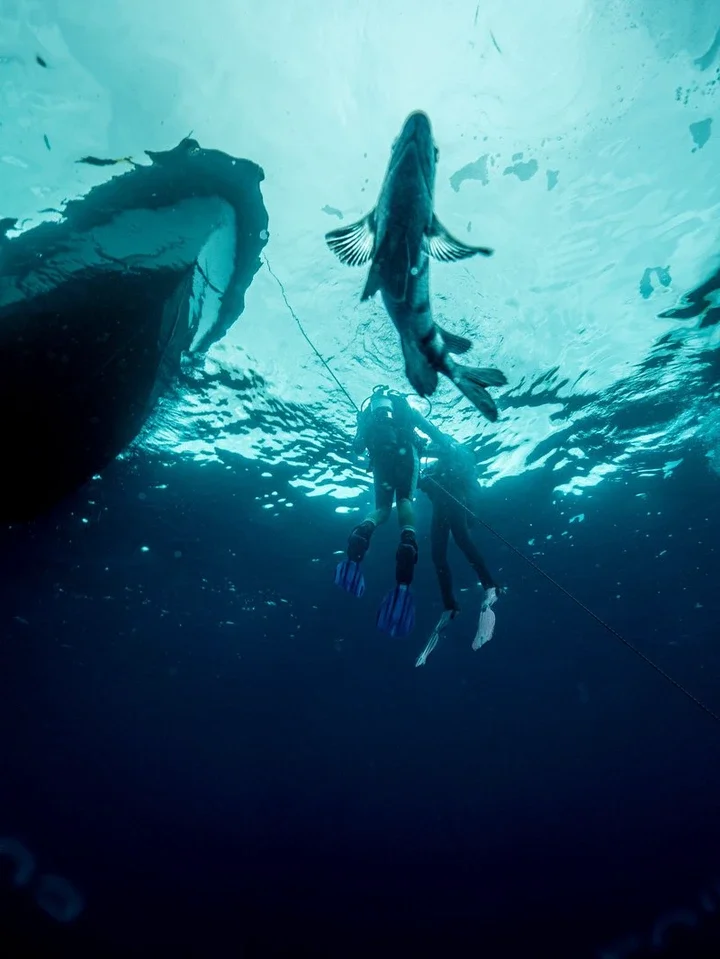

By the time the fruit platters and full English breakfasts are laid out buffet-style each morning, gardeners have already begun tending to the hibiscus topiary animals in Castle Gardens. The Mantis sits at the foot of Jacob’s Ladder, one of Saint Helena’s seven wonders. As its Biblical name suggests, it is a dizzyingly steep ascent-699 steps rising at a 45-degree angle-best tackled at sunrise or sunset, when the midday heat has eased and the valley is washed in its softest hues. Climbing the western slope, the view stretches across Jamestown, anchored by a whitewashed fort, the bay, and, on clear days, the silhouette of the Papanui beneath the water’s surface. The ship sank here in 1911, and each Friday-weather permitting-it has become something of a ritual for families to gather at the dock and swim out over the wreck. There, they hope for a glimpse of Saint Helena’s very own flounder, white seabream, wrasse, pufferfish, and blooms of orange cup coral-just a few of the 50 marine species found nowhere else on Earth.

Later, I take a boat out in search of the world’s largest fish: the whale shark. Saint Helena lies at the epicenter of a 445-square-kilometer marine protected area; its undisturbed, nutrient-rich waters are home to green turtles, devil rays, hammerhead sharks, and serve as a key migratory route for humpback whales. At one point, our vessel is encircled by a pod of pantropical spotted dolphins dancing in the surf.

While the whale shark’s deep-diving habits make it difficult to study, Saint Helena may offer a “missing puzzle piece” in our scientific understanding of these gentle giants, as Kenickie Andrews, marine conservation project manager with the Saint Helena National Trust, puts it. “From November to March, our island experiences one of the rarest phenomena-large gatherings of both mature male and female whale sharks,” he explains. “This gender mix is uncommon and offers researchers unique opportunities to study their behavior and potential breeding activities.” It also opens up extraordinary possibilities for eco-tourism, provided encounters are carefully managed: no touching, safe distances, and limited interaction times.

Eventually, the captain spots what we have been hoping for: a triangular dorsal fin slicing through the water. I slide quietly into the sea. At five meters long, this particular whale shark is modest by the standards of a species that can grow to more than three times that size. I watch as it combs gracefully for plankton, thousands of tiny teeth barely visible between its pursed lips-naturally curious, yet seemingly unbothered by my presence. As my 40-minute window draws to a close, the gentle giant’s pearl-like markings vanish into the deep blue below.

On the following day, within the grounds of Plantation House-the official residence of the governor of Saint Helena, and a name that starkly reflects the island’s colonial past-I am granted an audience with the world’s oldest known living land animal. Jonathan the tortoise, a rare Seychelles giant, has called this island home since 1882, when he was brought here by the British during Queen Victoria’s reign. Now estimated to be 192 years old, he has lived through 40 U.S. presidencies and eight British monarchs, and has been immortalized on the island’s coins and stamps. Despite his age, his glacial shuffles across the manicured lawn are interrupted by sudden bursts of energy at the sight of food-offering glimpses of the mischievous spirit once known for crashing tennis matches on the neighboring courts. Today, he shares his enclosure with three fellow tortoises, including his long-term companion Frederik, securing his status as a beloved local LGBTQ+ icon.

From the world’s largest and oldest animals to some of its rarest and smallest, Saint Helena hums with life across sea, land, and sky. On a hike to Blue Point with Tom Wortley of Rockmount Walking Tours (who, in true Saint style, is also a skilled plaster skimmer), I see the last five remaining wild Saint Helena ebony trees clinging to a crumbling cliff, alongside stands of endemic scrubwood. Located at the island’s southern tip, this trail offers views of dramatic coastal formations-the Gates of Chaos, Lower Black Rocks, and Lot’s Wife Ponds, naturally formed tidal pools fed by the Atlantic. Masked boobies, red-billed tropicbirds, and storm petrels nest in its craggy ledges while ethereal fairy terns circle above.

But it is the 420 endemic terrestrial invertebrates-tiny, often overlooked creatures-that account for much of the island’s biodiversity. Critically endangered species have also found refuge here, including European honey bees (free from the diseases devastating populations elsewhere); the spiky yellow woodlouse-a fluorescent creature the size of a fingernail that glows under ultraviolet light-and the golden sail spider. The health of the cloud forest that crowns Saint Helena’s peaks is monitored through the presence of these species, says Helena Bennett, director of the Saint Helena National Trust: “We also apply targeted methods to control the invasive species that prey on them.”

Saint Helena’s biodiversity has been under threat since the first known human arrival, beginning with the Portuguese in 1502. The island later passed briefly through Dutch hands before being settled by the British East India Company in the 17th century; today, it remains a British Overseas Territory. Colonizers plundered its natural resources, while feral rats, rabbits, cats, and grazing animals wreaked havoc on its fragile ecosystems. The sea reportedly turned black as fertile soil slid from steep inclines, no longer anchored by trees felled for firewood and tanning bark. Within decades, this once-verdant landscape had been reduced to arid shrubland. Although rainfall is scarce, many native plants have evolved to harvest moisture from the air; today, these freshwater reserves account for a third of the island’s supply-and once made it a vital port of call for ships crossing the infamous Middle Passage.

Colonialism’s environmental devastation mirrors its human toll: Saint Helena occupies a central place in one of history’s darkest chapters, the transatlantic slave trade. Following the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act, the British Navy began intercepting illegal slave ships and diverting them to the island. Between 1840 and 1872, more than 25,000 enslaved Africans were brought ashore. Though officially deemed “liberated,” many were transported onward to the British West Indies under systems of indenture. Of those who remained, nearly a third died shortly after arrival. Survivors endured overcrowded living conditions, food shortages, and forced labor.

In 2008, the remains of 325 individuals were uncovered during roadworks linked to the construction of the island’s airport. Four years later, Annina Van Neel-a Namibian-born environmental officer-arrived on Saint Helena as part of the project team, just as a far larger burial ground was unearthed in Rupert’s Valley, adjacent to Jamestown. Containing the remains of an estimated 5,000 formerly enslaved people, it is considered one of the most significant physical legacies of the slave trade anywhere on Earth. Van Neel eventually resigned from her position to work with the Saint Helena National Trust, where she developed a masterplan to ensure a dignified reburial and to help memorialize the island’s African heritage. Her mission-alongside renowned African American preservationist Peggy King Jorde and a group of islanders, many of them descendants of the enslaved-is at the heart of the 2022 documentary A Story of Bones.

Saint Helena is poised to become a place of return and reflection for people of African descent seeking to trace their heritage across the Atlantic. Bennett explains that, as part of the Transatlantic Slave Memorial Project, the National Trust plans to transform the No. 1 Building-constructed in 1865 as part of the Liberated African Establishment-into an interpretation center. “I hope that Saints, just like the greater descendant community connected to the history of the slave trade, are provided unfettered, decolonized access to this vital cultural resource,” Van Neel tells me. “Only then can reparations, restitution, and memorialization look like healing, reconnecting, and remembering our collective trauma and triumphs-in an inclusive, equitable, and non-destructive way that does not leave individuals and communities retraumatized or erased from the conversation.”

On Saint Helena, the healing of people and planet go hand in hand. For Saints-long marginalized and disenfranchised-this remote island in the South Atlantic is being reimagined not only as a place of memory, but of possibility. Perhaps the most visible symbol of that transformation is the Millennium Forest, which I visit toward the end of my stay. Launched in 2000, the reforestation project began with nearly every Saint purchasing and planting an Indigenous tree-gumwood, dwarf ebony, boxwood-on the site where the Great Wood once stood. Now, this semi-desert is slowly returning to green. A garden center supplies farmers and home growers with vegetable seedlings, fruit trees, and flowering plants. Between the young trees, the critically endangered wirebird-Saint Helena’s last remaining endemic vertebrate-can be seen foraging in the undergrowth; its population has more than doubled over the past two decades.

What is unfolding on Saint Helena is more than restoration-it is a living blueprint for how ecology and identity can be decolonized. Even with the new direct flight route from Cape Town, it’s an epic journey to get here. But for those willing to make it, it offers a chance to witness history being reclaimed-and a sustainable future being written.