Guarding the Golden Eggs: Why Ghana’s military must redeploy to defend its natural wealth – Kay Codjoe writes

By the mercy of time and the providence of conscience, the inner eyes of our nation are opening to its real war. I have walked among soldiers on parade and among the ruins of our rivers, the ghosts of our forests, and the hollow hearts of our mines. I have seen both the valour of men in uniform and the silence of dying rivers. The Ghana Armed Forces, heirs of a proud tradition, are today deployed not where our wealth lies, but by the roadside.

Obuasi, Tarkwa, and Dunkwa, our golden eggs, lie exposed, while men in fatigues salute traffic instead of defending treasure. The true frontlines of national defence are not our borders, but our rivers, forests, and mineral veins. Whoever guards these, guards Ghana itself.

Watching the recent engagement on galamsey, I was struck by how much of our defence architecture still lives by colonial geography. Soldiers are stationed along parade routes, while the gold, forests, and rivers, the arteries of national power, remain open and undefended.

When Franklin Cudjoe of IMANI asked about funding for the anti-galamsey war, he was right to question where the war chest is. But the issue is larger than budgets or bulldozers. The fight against illegal mining must trigger a complete reset of the Ghana Armed Forces’ geostrategy.

Across the world, the United States divides its defence posture into global geographic commands such as CENTCOM, AFRICOM, and INDOPACOM, each securing vital resources, routes, and spheres of influence. Those deployments sit on the corridors of oil, shipping, and commerce that define modern power. The world order itself is built upon such deployments.

Look inward. In Ghana, our battalions are still stationed by the roadside. Six Battalion, once in Takoradi, now in Tamale, from roadside to roadside. The Achiase Jungle Warfare School is perhaps the only forest still wearing a uniform. Meanwhile, the Obuasi goldfields, Tarkwa belt, and Dunkwa basin, the veins that feed the Republic, are stripped bare without permanent security.

History mocks us. When the British defeated the Asante, they built a garrison in Kumasi to secure gold, timber, and rail lines. That fort still stands today, now called a museum. We turned a military strategy into a tourist attraction.

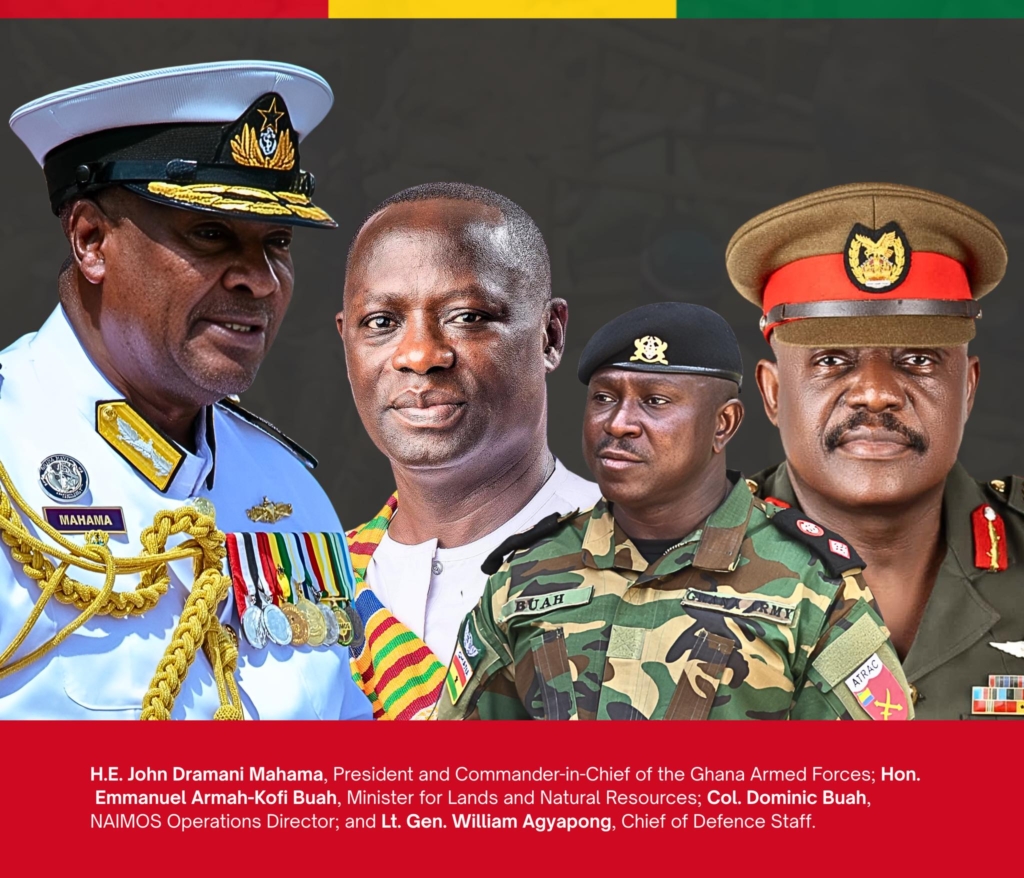

If we are serious about protecting our natural wealth, NAIMOS, the National Inter-Agency Taskforce on Illegal Mining, must be more than a stopgap. It should mark the beginning of a permanent redeployment of the GAF to guard our golden eggs. Every major gold belt, bauxite deposit, water body, and forest reserve should have a forward operations unit. It may take years to institutionalise, but the payoff would be a Ghana whose wealth is defended as jealously as its borders.

This is not militarisation; it is a constitutional duty. Civilian oversight must remain absolute: the GAF secures the field, while NAIMOS, the EPA, and the judiciary secure accountability. The mission must protect both the land and the law.

If the Ghana Armed Forces ever said “no” to galamsey, there would be no galamsey. The GAF already has the full spectrum of land, air, and water power to neutralise illegal mining anywhere in the country. Engineers can deny access, aviation can surveil, riverine units can interdict, and logistics can hold territory. The capacity exists; what is missing is strategic alignment and mission clarity.

The current NAIMOS plan offers a starting blueprint, the nation zoned into seven regions and twenty-one sectors, twenty-four-hour patrols, drones, and four hundred troops already deployed. That is how a state begins to move from rhetoric to readiness. But let us not pretend this will be cheap. The 2023 Auditor-General’s report estimated that Ghana loses over GH¢3 billion annually to illegal mining, nearly double the entire capital expenditure of the Defence Ministry that year. The real question is not whether we can afford this fight, but whether we can afford to keep losing it.

This is not to deny the social roots of galamsey. Poverty and unemployment are real. But poverty cannot justify poisoning rivers. Just as food security depends on agricultural defence, ecological security must now depend on military strategy. The GAF protects not wealth for the rich, but water for the poor.

As President Mahama himself said, a state of emergency may be declared if the National Security Council so advises. The redeployment of the GAF could form the very foundation of that advice, a proactive posture rather than a reactive decree. A state that defends its soil defends its sovereignty.

A resource-centric GAF posture will require both doctrine and a war chest. It will demand a merger of intellect and force. As Lt. Gen. Sir William Francis Butler warned in 1889, “The nation that insists on drawing a broad line between the fighting man and the thinking man will have its fighting done by fools and its thinking by cowards.”

Our soldiers must therefore think geopolitically. The battle for Ghana’s environment is not only ecological; it is economic, cultural, and strategic. Whoever controls the rivers controls the food chain; whoever protects the minerals protects the currency; whoever guards the forests guards the rain.

So yes, Franklin Cudjoe was right to ask about the money. But money without mission is a waste. The mission must be clear: redeploy the Ghana Armed Forces to defend the nation’s resource corridors permanently. This is not about creating a new or permanent NAIMOS-GAF structure; it is about restoring constitutional order within the defence establishment and realigning it to its true national security function.

If the GAF operates under a UN mandate to protect natural, cultural, and human resources, Ghana must uphold that same duty at home. What our troops execute abroad, they must perfect within our borders. The soldier who guards a UN medal must also guard a Ghanaian river.

Until our soldiers sit where our wealth sits, we will continue to chase excavators with press conferences and lose rivers with parliamentary speeches. If we cannot afford to defend our gold, then we cannot afford to call ourselves rich.

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of Multimedia Group Limited.

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of Multimedia Group Limited.

Source link