Weak health systems, late diagnosis kill half of breast cancer patients in Ghana annually – WHO data

Every October, the world turns pink. Streets, skylines, and social media feeds are filled with ribbons and campaigns for Breast Cancer Awareness Month, urging women to examine their breasts, seek screening, and stand in solidarity. Yet behind the global movement lies a sobering truth: breast cancer remains the most common cancer among women worldwide and one of the leading causes of cancer deaths. In countries like Ghana, the disease is not only widespread but also devastating, claiming nearly half of the women diagnosed each year.

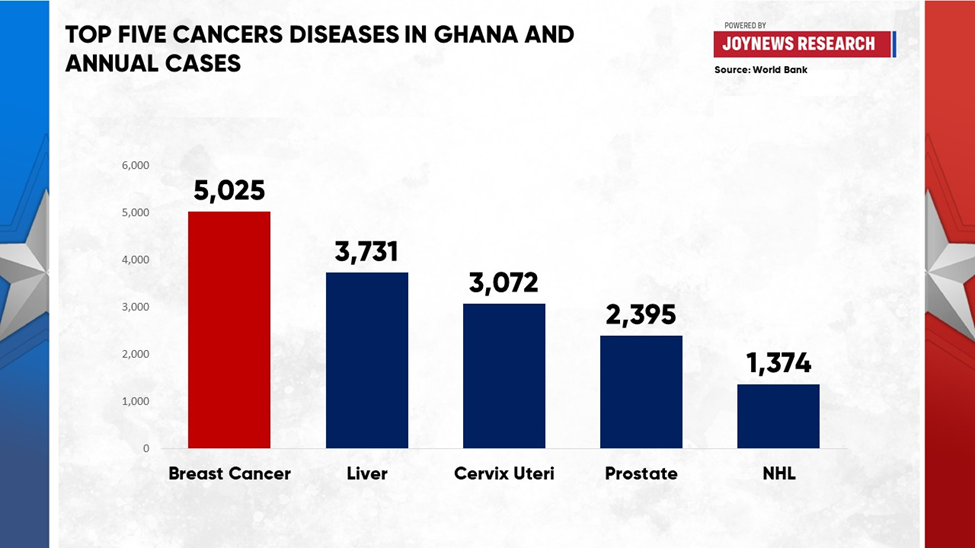

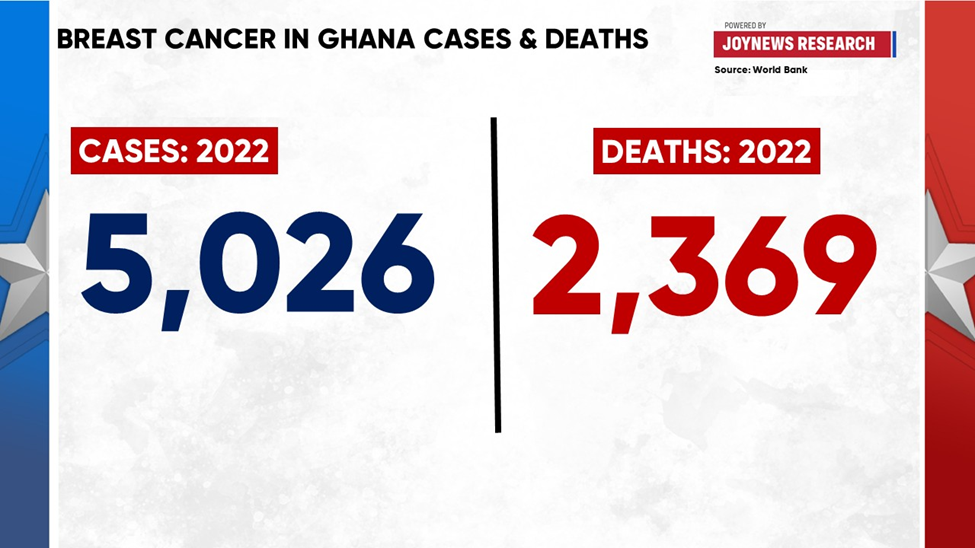

In Ghana, breast cancer has emerged as the number one cancer in both incidence and prevalence. According to Global Cancer Observatory data on Ghana, there were 5,025 new cases in 2022, representing 18.4% of all cancers diagnosed in the country. Tragically, 2,369 women died, accounting for 13.2% of all cancer deaths.

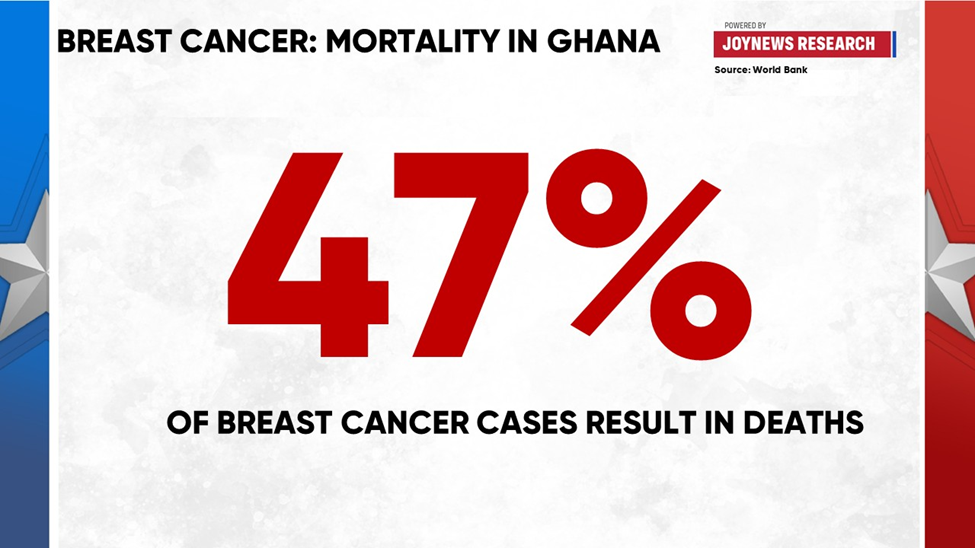

This translates into a case-fatality rate of nearly 47%, meaning that for every two Ghanaian women diagnosed, one does not survive. Beyond mortality, the burden continues in survivorship: an estimated 13,385 women are living with breast cancer within five years of diagnosis, the highest five-year prevalence of any cancer type in the country. Breast cancer is therefore not only Ghana’s most common cancer but also the second leading cause of cancer deaths after liver cancer.

The limitations of the health system worsen the crisis. Ghana has just six main cancer treatment centers, three public and three private. Public facilities are chronically overstretched, while private centers often charge fees that remain out of reach for most families. The country faces severe shortages of oncologists and pathologists, long delays in obtaining pathology results, and limited access to radiotherapy. These barriers mean that many women begin treatment far too late, or not at all, contributing to poor survival outcomes and deepening the emotional and financial toll on families.

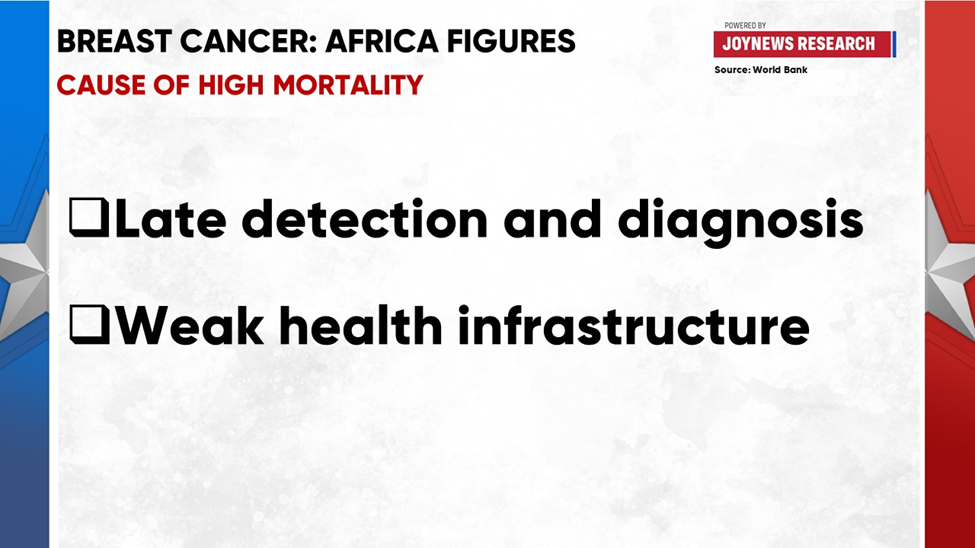

This reality is echoed across Africa, where breast cancer is now the most common cancer overall and the leading cause of cancer death in women. In 2022, the continent recorded 198,553 new cases, accounting for 16.8% of all cancers, and 91,252 deaths, representing 11.9% of cancer deaths. At the same time, Africa carries the continent’s largest share of survivors, with 507,659 women living with breast cancer within five years of diagnosis, the highest prevalence for any cancer type.

On paper, Africa appears to have the lowest incidence rate worldwide, at 38 cases per 100,000 women compared to 54 globally. But the paradox is clear: it also bears the highest mortality rate at 19.2 deaths per 100,000 women. The explanation lies not in biology but in systemic barriers, minimal screening programs, delayed diagnoses, limited access to oncology services concentrated in urban centers, and treatment costs that remain unaffordable for most families.

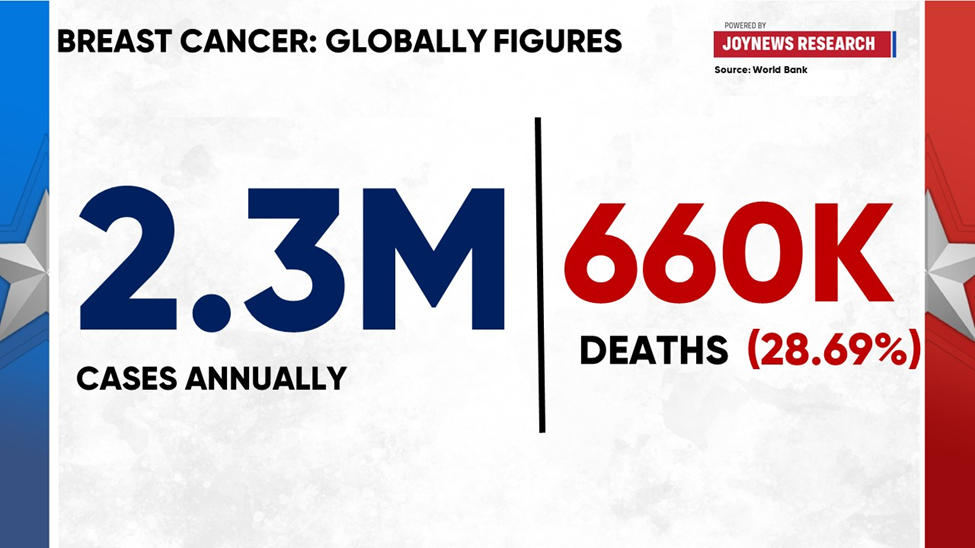

Globally, breast cancer occurs in every country and in women of all ages after puberty, though rates rise with age. In 2022, an estimated 2.3 million women were diagnosed, and 670,000 died, making it the most diagnosed and most prevalent cancer worldwide. It was also the most common cancer among women in 157 of 185 countries. While 99% of cases occur in women, men are not exempt: about 0.5–1% of breast cancers occur in men, who are treated under the same principles of management. Strikingly, roughly half of all breast cancers develop in women with no specific risk factors beyond sex and age, although other factors such as obesity, alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history, radiation exposure, and hormone therapy after menopause also increase risk.

The global age-standardized incidence rate is 54 per 100,000 women, while the mortality rate stands at 12 per 100,000. Yet outcomes vary dramatically depending on where a woman lives. In high-income countries, survival rates reach 85–90% thanks to structured screening, early detection, and access to advanced therapies and reconstructive care. In contrast, survival in many African countries hovers around 40–50%, reflecting deep inequities in healthcare infrastructure. The same disease that is treatable and often survivable in wealthier nations becomes a leading cause of death in low- and middle-income settings, where women face delays in diagnosis, limited treatment access, and high out-of-pocket costs.

The future projections are sobering: by 2040, 60% of new breast cancer cases and 70% of deaths will occur in low- and middle-income countries. Ghana ranks 11th among African countries with the highest breast cancer prevalence, mirroring the continental trend of lower incidence but disproportionately high mortality. For Ghanaian women, survival is not determined solely by the biology of the disease but by whether they can access affordable care, overcome stigma, and receive timely treatment.

What makes breast cancer particularly dangerous is not only its prevalence but also its progression. Cancer begins inside the milk ducts or lobules and may initially remain localized and non-life-threatening. If untreated, it can invade surrounding tissue and metastasize to lymph nodes or distant organs such as the lungs, liver, brain, or bones. Early diagnosis is therefore critical. The World Health Organization emphasizes two key pillars of detection: early diagnosis based on awareness of symptoms (such as breast lumps, changes in breast shape, or nipple discharge) and population-level screening, typically mammography for women aged 50–69, to detect disease before symptoms appear. Most breast lumps are not cancerous, but when malignant tumors are found early, they are far more treatable.

Treatment is tailored to the type and stage of the cancer. It often involves a combination of surgery, radiotherapy, and medicines such as chemotherapy, hormone therapy, or targeted biological drugs. Advances in treatment mean that many women with hormone-positive cancers can now take oral endocrine therapies for 5–10 years to halve recurrence risk, while HER2-positive cancers respond to targeted drugs like trastuzumab. Radiotherapy, meanwhile, plays a vital role in preventing recurrence and in preserving the breast in early-stage disease. Yet even the most effective therapies only save lives when they are accessible and completed in full, a challenge in many low- and middle-income countries where patients often cannot afford treatment or must abandon it midway.

The inequities are stark. In countries with a very high Human Development Index (HDI), one in twelve women will develop breast cancer during their lifetime, but only one in seventy-one will die from it. In countries with low HDI, by contrast, only one in twenty-seven women will develop breast cancer, but one in forty-eight will die. In other words, women in wealthier nations face higher chances of diagnosis but far greater chances of survival. Women in poorer countries face a lower incidence but much deadlier outcomes.

To confront these inequities, the World Health Organization launched the Global Breast Cancer Initiative (GBCI) in 2021. Its goal is to reduce breast cancer mortality by 2.5% per year, ultimately preventing 2.5 million deaths by 2040. The plan rests on three pillars: promoting health and awareness for early detection, ensuring timely and accurate diagnosis, and guaranteeing access to comprehensive management, rehabilitation, and palliative care. Countries that succeed in implementing these pillars have already achieved annual mortality reductions of 2–4% over recent decades.

The lesson is clear: survival is possible. But it depends on strong health systems, timely detection, and access to treatment. Ghana’s statistics, Africa’s paradox, and the global data all point to the same truth. Breast cancer is more than a disease; it is a measure of how societies value women’s health and how health systems respond to preventable deaths.

Awareness campaigns remain vital, but awareness without access is hollow. Pink ribbons should symbolize not only solidarity but also a demand for action to invest in early detection, expand treatment centers beyond urban hubs, train more specialists, and make care affordable for all. The breast cancer crisis in Ghana, in Africa, and around the world is not inevitable. It is the result of choices, investments, and priorities. With urgent reforms, survival rates can rise, grief can be spared, and millions of women can live beyond a diagnosis.

All of this reveals a central truth: breast cancer is more than a medical condition. It is a test of how societies prioritize women’s health and how health systems respond to preventable deaths. Awareness campaigns are important, but awareness without access is hollow. Pink ribbons should symbolize not just solidarity but also a demand for action to invest in early detection, expand treatment centers beyond major cities, train more specialists, and make care affordable for all.

The breast cancer crisis in Ghana and across Africa is not inevitable. It is the result of choices, investments, and priorities. With urgent reforms, survival rates can rise, grief can be spared, and thousands of women can live beyond a diagnosis.

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of Multimedia Group Limited.

Tags:

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of Multimedia Group Limited.

Source link