Bright Simons : The OSP wants to jail former NPA Bosses, but Katanomics is the Bigger Culprit

The Office of the Special Prosecutor (OSP) is prosecuting former senior officials of the National Petroleum Authority (NPA), one of the big government agencies in Ghana’s energy sector.

The OSP alleges that the former NPA Executives created an extortion racket that netted them more than $25 million in corrupt funds.

In recent days, a loud political controversy has been raging over whether or not any of the nearly $10 million worth of assets across Ghana, ranging from giant trucks and fuel stations to luxury condos, reported to have been frozen by the OSP in the course of its investigations, belong to the former Chief Executive (CEO) of the NPA.

Precious little, however, has been said in the media about the actual mechanics of the alleged “extortion racket” or “corrupt scheme” for which the former NPA CEO and his colleagues are being tried. Except that it relates to this program: UPPF, the Unified Petroleum Pricing Fund.

Katanomics is the game

As I tried to explain in the Pwalugu Dam case, Ghana suffers from a condition of Katanomics, such that citizens get trapped in the politics of every issue and are unable to look underneath and see the more pernicious policy problems festering and metastasing.

Much of what gets waved about as “corruption” in Ghana have their origin in disjointed, poorly analysed, and badly executed policies that virtually no citizen groups keep an eye on. The lack of “critical citizen audiences/constituencies” for policy matters, and the resulting inability to “positively politicise policy matters” has created a massive incentive for waste and abuse of public funds through all manner of shady schemes wrapped in shallow, seemingly well-intended, cloaks. This, in simple terms, is what I call Katanomics.

Let’s break down the whole UPPF charade to illustrate my argument

Consider the map of Ghana. From the southernmost tip around Princes Town and Dixcove (i.e. Cape Three Points) to the northernmost extreme in Pulmakom around Pusiga, Ghana stretches for about 672km.

One thing most of us don’t notice is that the price of fuel on the pump is usually uniform within a brand chain across Ghana, but nobody mandates that all retail brands (e.g. Puma, Star Oil, Goil, Total, Shell, etc.) charge the same price. That is to say, a liter of fuel sold by Allied in Tema Community 2 would normally be priced the same as a liter of fuel sold by Allied in Kintampo. According to the official government stance, UPPF is the reason why.

As the NPA has explained often when the UPPF and other margins it imposes on fuel prices come under attack, until the UPPF was introduced in the 1990s, “uniform pricing of petroleum did not exist” in Ghana.

Together with the “Primary Distribution Margin” (PDM), the UPPF is a vestige of price control in Ghana’s “managed” deregulation of the downstream petroleum sector (the part of the industry where ordinary consumer buy fuel on the pump, such as the Shell and Total retail outlets). It works like a kind of tax added to the price of fuel consumers buy. The monies are collected from the fuel retailers and pooled into a fund controlled by the NPA. The NPA is then supposed to distribute the funds to transporters carting fuel across the country. By so doing, it equalizes freight costs across Ghana and ensures that consumers are not penalized by geography.

Sounds reasonable, right? Brilliant, even. Who can be against a policy meant to ensure that Bolga residents merely for living far from the ports on the coast through which fuel enters into the country don’t pay more for petrol than residents of Sekondi and Akosombo?

But nothing is ever as it seems

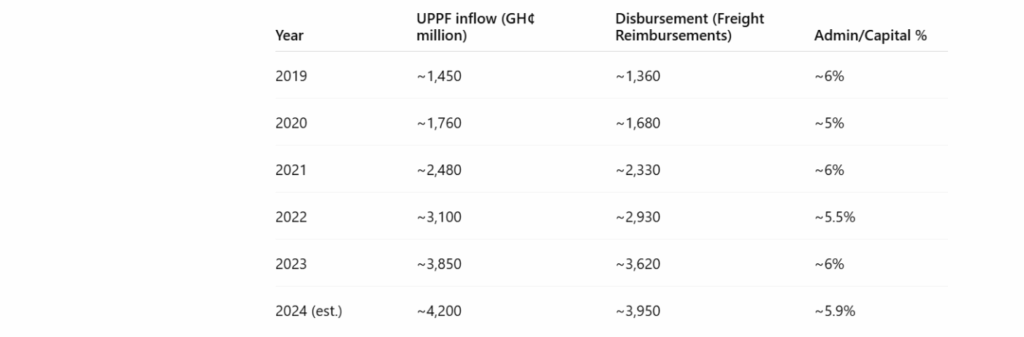

The first hint that something may have gone awry was when the NPA simply refused to publish any reports about how much it was collecting into the Fund and how, how much, and to which transporters exactly it was sharing these funds with. No information has ever been provided on the administrative costs of managing the UPPF Fund either. At least not since its latest incarnation in 2005.

In recent pricing windows, the taxes/levies/margins together have amounted to about GHS 4.25 – 4.27 per liter, with the UPPF increased at one point from about GHS 0.36 to GHS 0.47 (it stayed at 0.9 for long stretches of 2024). That puts UPPF at roughly 10% – 21% of the tax stack on fuel and about 3.4% – 7% of the ex‑pump price. An estimate of proceeds in 2023 came to about GHS 1.5 billion. In 2024, most estimates averaged over GHS 4 billion. Today, it certainly exceeds GHS 2 billion per year in annual yield for the NPA. A line this big cannot be run on good intentions; it needs open accounting, operational benchmarks, and a sunset logic tied to measured reductions in GHS/Litre logistics. Well, not in Ghana.

Besides accountability, there is the issue of actual efficacy. Like many policies with a veneer of good intentions in Ghana, the actual logic behind UPPF isn’t actually very deep when you probe.

Brand Power vs Logistics

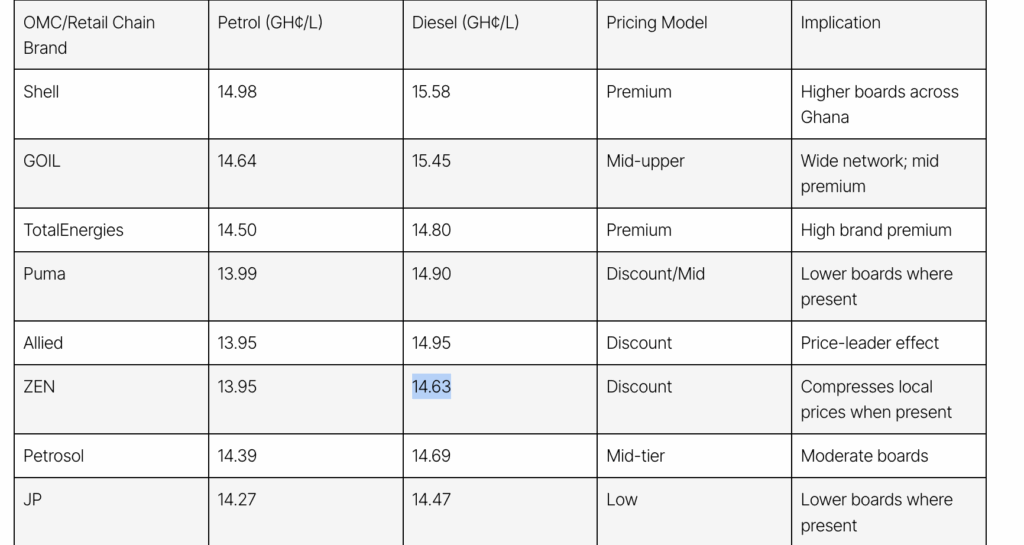

Ghana’s liberalisation of fuel pricing over the years did not merely seek to restrain state price‑setting. It also led to the liberation of retail branding strategy. The National Petroleum Authority (NPA) may require each OMC (as retail chain brands are officially known) to keep a single ex‑pump price nationwide for its own outlets, so the Shell price in Accra must match the Shell price in Wa. It may even assign credit for such an outcome to its PDM and UPPF policies. But nothing says that Shell must price like Puma, or Allied like TotalEnergies. Whatever price uniformity exists by policy fiat only holds water when comparing outlets within the same retail chain brands, not across the market.

For citizen-consumers, the stark reality is that a “single national price” is an illusion. The idea of a “uniform price” secured through opaque funds like UPPF and the PDM stash is pure “state enchantment.”

Across several pricing windows in 2024, the spread between the cheapest and most expensive petrol often hovered around one cedi per litre; diesel spreads were sometimes larger. These differences are, obviously, not the result of tanker mileage or axle count. They exist regardless of distance considerations. They are, to keep it simple, driven by brand differentiation in a near-deregulated landscape.

In dense urban areas where many brands cluster, choice can create a sense of consumer sovereignty. In Bongo, Zabzugu, or parts of Nzema East where only a few retailers are present, and only one or two may be considered “premium”, consumers often face a contest between a pure price focus and perceived quality. Buying the lowest-priced fuel is not always a choice even when available. Equalisation Funds like UPPF and PDM do not change any of these dynamics shaping the cost felt by the end-consumer.

And that is even assuming that the money in such equalization funds were all equitably distributed to transporters in ways and manners that actually reflect the geographical constraints of distributing fuel to far-flung parts of Ghana. Bold wishes, given what the OSP has to say about the corruption surrounding UPPF management.

At any rate, we know that in some years, over $100 million is distributed out of the UPPF pot to IT contractors of the NPA. That is proof positive that not all the money goes to “equalise freight.” We have also been told about funds from the stash being used to pay for fuel used by some security services, etc.

Some analysts have suggested that it has become undeclared policy that excess funds after reimbursing transporters for costs incurred in fuel cartage may go to municipal authorities for development spending.

This is all very weird as the law mandating the setup of the UPPF (Act 691) is very clear that the funds from the Fund may only be spent on freight reimbursement, infrastructure to reduce freight cost variance, and Fund administration.

The NPA’s extremely high-level accounting also attempts to show that virtually all the money has gone into freight cost reimbursement for price equalisation purposes.

Distance undeniably matters in logistics. But distance is predictable, while competition is lumpy. A place can be far and still have a competitive market (e.g. Tamale), or relatively close to the ports and yet be poorly served by transporters and retailers alike, and thus commercially captive (think of Dzelukope, Twifo, and Ahanta). The current policy may benefit Tamale, on top of its other advantages, but it does little for those truly deprived areas if price-aggressive retail players choose not to site there and inefficient transporters are the only ones who bother to deliver fuel regularly.

Do you even need Equalisation Funds to subsidise consumers in far corners?

Most fuel products in Ghana enter primarily through the ports in Tema and Takoradi. The most elegant idea would thus be to move bulk fuel cargos north on a discounted lake spine, for example via the Akosombo to Buipe stretch and then complete the journey by pipeline or road to Tamale, Bolgatanga, and the border towns.

The problem right now is that chaos reigns over river and lake transport in Ghana today. Downtime, shallow stretches, ferry cycles, and road vulnerabilities have all conspired to create a mess.

If Ghana truly wants to bring down the structural cost of distance, it must do two boring things: move more liters by the cheapest mode, and keep that mode reliably boring. The Akosombo – Buipe leg is a discount conveyor belt, yet for years policymakers have underutilized the asset. Road haulage remains indispensable, but it should not be the default for the long leg if a cheaper conveyor exists.

Certainly not when water transport can be 10x cheaper than road transport at certain volumes and distance measures. In one pricing window recently, Volta Lake Transport Company quoted GHS 48.40 per ton for the 415 km Akosombo – Buipe leg in one of its haulage schedules, which works out to ~GHS 0.116 per ton-km. For a 1,000-liter cargo, that is roughly GHS 41 per 1,000 litres, i.e., ~GHS 0.04 per liter, compared with GHS 0.45 per liter via road. Imagine water transport for most of the North-South stretch of the country.

Ghana is not really that big. The country’s poor logistics network is what sometimes amplifies the effect of distance on pricing.

The Volta Lake spine’s operational history, for instance, spins for us a chronicle of unrealised potential. In 2009, after dredging and modest berth upgrades, the Akosombo – Buipe cycle briefly hit an enviable rhythm, moving more than 70 million liters of fuel across a season with turnaround times that gave wholesalers confidence to plan inventory.

By 2014, however, fluctuating water levels, tug maintenance delays, and sporadic labour disputes had stretched the average cycle from seven days to twelve, and sometimes twenty. Each additional day added a silent surcharge: interest on working capital, demurrage disguised as waiting time, and pricing risk pushed back onto the retailer. When barge utilisation fell below 55 percent, marketers quietly shifted long hauls back to road, and the system lost its cheapest leg with nary a protest from any quarter.

Downtime episodes have ripple effects. In 2018, a three‑week low‑water episode forced a full switch to road on the northern corridor. The immediate logistics uplift jumped from roughly five Ghana pesewas per liter to twenty‑eight. A month later, after axle‑weight enforcement tightened, it climbed to forty‑two Ghana pesewas.

In 2021, a tug failure coincided with a diesel price spike; the all‑road alternative hit sixty pesewas per litre for some consignments.

None of these surges showed up as a special line on the pump. They were buried in retail chain brand‑level averaging and passed on unevenly across districts, reinforcing the illusion that distance had been equalised when, in fact, volatility had simply been socialised.

Then there is the issue of fairness

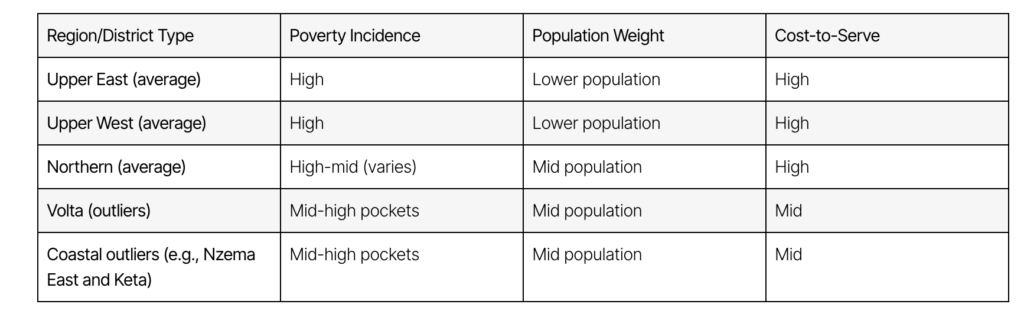

The moral case for price equalisation stands or falls on the map. Ghana’s multidimensional poverty is concentrated in the North, yes, and the distance-subsidy logic of policies like UPPF and PDM naturally ride on that coincidence: the places most vulnerable to the high transport cost = higher fuel cost problem also happen to be in the North.

But there are many southern districts whose deprivation rivals poorer northern municipalities. Making poverty distribution and its coincidence with fuel-overpricing due to logistics-strain strictly about distance would miss the point.

For example, Krachi East and parts of Oti bear high poverty with average retail outlet density and variety. Ada East and Keta combine coastal proximity with considerable pockets of deprivation. Nzema East presents a coastal outlier where retail outlet variety is thin whilst poverty effects are thick. A targeting matrix that blends poverty incidence, station density, and freight‑to‑retail pass‑through would paint a completely different picture from what the logic behind UPPF has been scripting.

It is important to take a cue from how big companies in the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) space, where consumers are highly sensitive to pricing, tackle the same issue of the effects of logistics on pricing. Using multimodal transport-route optimisation tools, hub-and-spoke distribution networks, and various last-mile supply chain strategies, these companies are able to maintain relative price uniformity across a very heterogeneous group of retailers.

Consider that even in a counterfactual Ghana where there was no UPPF, the added cost of unharmonised transport pricing for fuel in Bolgatanga versus Tema would be just about GHS 0.20 to GHS 0.70 pesewas. A price margin easily wiped away by inter – retail chain competition or a shift to water transport in vital segments of the supply chain. At any rate, should the need to shield Bolga residents from 20 pesewas extra cost on fuel justify all the confusion and chaos surrounding UPPF, not to talk of the suspected/alleged corruption?

In the context of this problem, the private sector has had decades to refine solutions in far more complex settings. What the NPA is trying to manage with fuel price harmonization across Ghana is child’s play by comparison. Instead of learning from these players, shady schemes have been erected to reinvent the wheel. All funded by surcharges on poor citizen-consumers.

As usual, the real policy-solutions capable of reducing transport and logistics surcharges on fuel prices are boring and analytical.

The Way Forward

First, there must be transparency. Any public money spent on addressing the problem, whether from levies and margins or elsewhere from the public purse, must be fully and thoroughly accounted for. Through a citizen dashboard, as one example.

Second, the primary area of spending should be to lower the cost of connecting mega-depots at strategic geographical points in the country. UPPF funds could well be spent on major lake and river transport enhancements, for instance.

Third, the freight map of the country should be open-sourced, regularly updated, and operated based on rigorous market data. When that is done, zonal logistics & freight pricing bands should become easy to compute by anyone wishing to enter the industry (with the added benefit of banks and other financiers having the visibility they need to price transport asset financing packages.)

Fourth, any actual subsidies deemed necessary must be based on such open-freight pricing benchmarks and distributed on the basis of auctions, bids, and other competitive measures.

Today in Ghana, uniform pricing is a slogan but seeking real equity is an engineering problem. Therein lies the contradiction.

Applying the engineering lens opens a vista of practical possibilities. Officials know exactly what to do. They know that we must finish the Buipe – Bolga line and publish its uptime; create municipal pad auctions so discount retailers can enter high‑poverty districts without begging for land; and reserve rebates for essential fleets whose movement connect with clear public good.

The only reason they don’t bother and keep coming up with shady schemes instead is because they know that Ghana doesn’t have a critical mass of policy-interested citizens paying attention. Only politics command interest, even among the upper middle classes. Policy never does. In short: Katanomics.

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of Multimedia Group Limited.

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of Multimedia Group Limited.

Source link