The Galamsey Chronicles: Illegal Mining and the Fate of a Nation: (Episode 8/10)

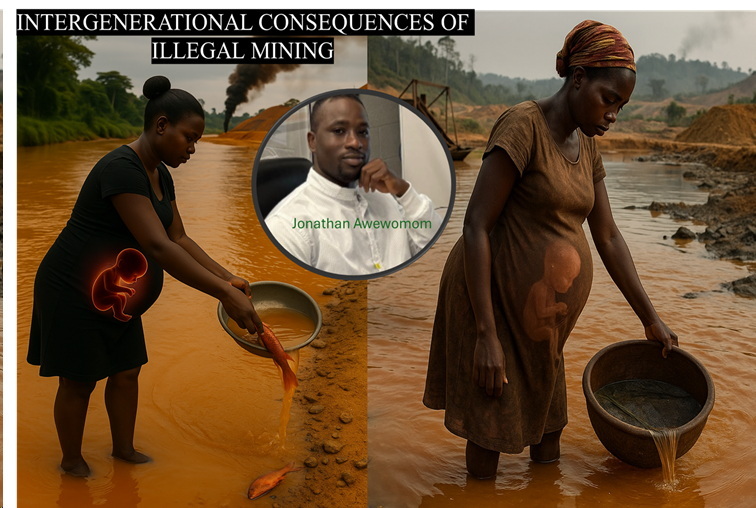

Intergenerational and Social Consequences of Galamsey (illegal Mining)

Ghana’s welcome is generous but mercury-laced rivers, arsenic-rich soils, and cyanide-scarred aquifers do not forget. The deepest harm of galamsey is not the spectacle of muddy water today; it is the quiet inheritance of disease, lost cognition, broken livelihoods, and mistrust that tomorrow’s children receive.

Environmental footprints that outlive the mine

Mercury (Hg) → methylmercury (MeHg) in food webs

Elemental/ionic Hg used for amalgamation is converted by microbes to MeHg in sediments and water. MeHg biomagnifies up aquatic food chains, persisting in fish and in people long after pits are abandoned. Chronic exposure is linked to neurodevelopmental injury (attention, memory, motor and visual deficits) and cardiovascular risks. These effects are most severe for fetuses and children.

Arsenic and Pb in Soil & Dust

Disturbed laterites and tailings release As and Pb that can remain for decades to centuries, with variable but often substantial oral bioavailability especially in fine dust fractions that children ingest or inhale. Such metals are proven carcinogens and neurotoxins, with strong links to kidney damage, anemia, and impaired brain development.

Cyanide and daughter products in water

Although, Free cyanide typically breaks down within days to weeks in sunlight, it can persist and transform into other toxic cyanide complexes, sustaining risk to drinking-water aquifers and connected streams. When spills infiltrate groundwater or bind with metals to form stable cyanide complexes in tailings, they can persist for months to years, prolonging exposure risks. The rate of breakdown is strongly influenced by environmental factors such as pH, sunlight, and the presence of metals, meaning some sites can remain hazardous long after mining stops

How long do contaminants stay?

- Mercury/MeHg: In aquatic sediments and living organisms, mercury undergoes microbial conversion to methylmercury (MeHg), a highly toxic and bioavailable form. This MeHg does not simply dissipate; it remains active in the environment for years to decades, cycling between water, sediments, and the food web. Because MeHg bioaccumulates in individual organisms and biomagnifies up the food chain, the highest concentrations are often found in predatory fish and wildlife consumed by humans. Paradoxically, the health risk frequently peaks after mining stops, as stored sediments are resuspended during floods or erosion events and as aquatic food webs gradually rebuild, leading to renewed uptake. This delayed exposure means that communities can continue to face elevated MeHg risks long after visible mining activity has ceased, impacting future generations through maternal–fetal transfer and chronic dietary exposure.

- Arsenic/Lead: These metals are elements and therefore do not degrade over time, making them effectively persistent in soils. Their chemical form (speciation) and how easily they are absorbed by plants or humans (bioavailability) can shift due to changes in pH, redox conditions, or microbial activity, sometimes making them even more mobile and dangerous. Without deliberate remediation measures such as soil washing, immobilization, or excavation, their natural attenuation is extremely slow, often measured in decades or longer. As a result, contaminated sites can remain a source of exposure for multiple generations

Intergenerational health chain: from pit to placenta

The intergenerational health chain of galamsey-related contamination begins with the environmental reservoir, where mercury (Hg), arsenic (As), and lead (Pb) accumulate in sediments, soils, dust, and groundwater, creating long-term sources of exposure. These contaminants then find pathways to people: methylmercury (MeHg) enters through fish and bushmeat from polluted waters, arsenic and lead through household water and crops irrigated with contaminated sources, and airborne dust from shafts and processing sites contributes additional exposure. Once inside the human body, these toxicants can cross from mother to child; MeHg and Pb readily cross the placenta, and early-life exposure has been linked to lower IQ, attention and behavioral disorders, growth restriction, and congenital anomalies. Beyond immediate health impacts, epigenetic and transgenerational effects have been observed, with lead and other toxicants leaving heritable epigenetic changes that may affect subsequent generations even after direct exposure has ceased. This chain indicates how the legacy of galamsey can echo biologically through time, shaping health outcomes far beyond the present generation.

Social consequences for communities and the nation

- Education & child development: Chronic metal exposure is associated with reduced cognitive performance; in mining districts, schools face absenteeism and dropouts amid in-migration and informal economies. Evidence from Ghana and West Africa links ASM booms with women’s abuse, drug abuse, and high in-migration; child labor risks remain a recurring concern

- Livelihood shocks: Silted rivers and polluted irrigation water reduce cocoa and food yields; households face medical costs and loss of labor capacity, eroding intergenerational wealth. Nationally, pollution and lost taxation from illegal gold extraction drain billions and threaten water security.

- Public trust & governance: Perceived impunity for financiers/enablers, and fragmented enforcement, corrode confidence in institutions and fuel community conflict.

What must change

- Protect the unborn first: Prioritize mercury-free gold technologies and restrict Hg supply; expand fish consumption advisories and safe protein alternatives where MeHg is high.

- Remediate, don’t just raid: Fund sediment management, tailings stabilization, and contaminated-soil caps near schools and farms; monitor MeHg in fish and As/Pb in household dust with open data.

- Health systems response: Routine maternal/child metal screening in hot spots; neurodevelopmental follow-up and nutritional countermeasures (iron, selenium, calcium) to reduce uptake.

Bottom line: Galamsey’s most tragic product is not a bar of illicit gold, it is the invisible debt of toxic exposure that our children and their children must pay. The chemistry is unforgiving; so must be our protection of future Ghanaians.

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of Multimedia Group Limited.

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of Multimedia Group Limited.

Source link